Editor's note: This article is part of "The Ten Today," a series that examines the Ten Commandments in modern society. This story explores the sixth commandment: "Thou shalt not kill."

As a boy, Will Fields wanted to be a scientist. He had a chemistry set, a telescope and a microscope with slides, and for Christmas he once asked for math flash cards. He went to school at Brentwood Science Magnet School near Beverly Hills.

But, he didnt live there. Each morning he took a bus from his home in South Central Los Angeles up Interstate 405, past the airport, past Santa Monica and into the Brentwood hills. Each afternoon he went home to his neighborhood of run down streets, crack addicts on the corners, homes without fathers, communities without jobs and gang warfare everywhere.

You start to realize your place in life, Fields says. You see that youre at the bottom of the barrel. This your lot. This is going to be your life. As a child its frightening to see that reality.

And so the tide pulled him along. As Fields grew older, he got kicked out of multiple high schools for fighting. Then he was doing strong-arm robbery and battling other gangs for respect. Arrested when he was 19, he pled guilty to three counts of attempted murder. He spent the next six years in prison.

Fields came of age in a dangerous time and place. When he was born in 1981, the U.S. homicide rate had doubled to 10.2 per 100,000 from 4.6 in 1963. Through his boyhood, murder rates stayed high dipping to 7.9 in 1984, surging to 9.8 in 1991, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

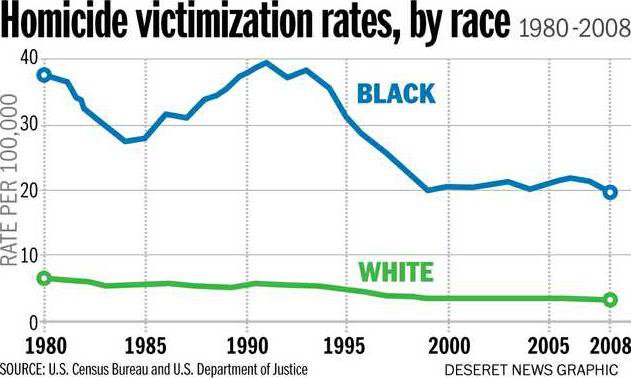

But the national murder rate misses the crux of the story. Homicide in America disproportionally involves young African-American males, both as victims and offenders, and the disparity is enormous. From 1980 to 2008, victimization rates for blacks were six times higher than for whites. Offending rates were eight times higher.

In 1993, the year Fields turned 12 and began running with a gang, the murder victimization rate for black males between 18 and 24 years old stood at a whopping 196 per 100,000 compared to 19 per 100,000 for white men of the same age.

Then, to everyones surprise, murder rates tumbled, falling from 9.5 per 100,000 in 1993 to 5.5 in 2000. While most people blame crack cocaine for the spike during Will Fields boyhood, no one is totally sure why violence fell so sharply during his teens.

As the nation has taken stock of how the commandment to not kill is reflected in modern law and society, researchers have struggled to understand why homicide rates remain so high among impoverished urban black youth. Answers remain elusive, but two recent large studies offer some intriguing suggestions. A New York City study considers how effective police work can temper street violence. The other, based in Chicago, focuses on the role of poverty, neighborhoods and family structure in shaping or mitigating it.

Kill or be killed

For Will Fields, the disconnect between his tony school and his squalid streets and home life wore him down. Mocked by friends for using big words, he got no encouragement for his academic hopes. He rarely saw his father. His mother struggled to raise two boys, who as they grew became too much for her to handle.

In the end, he found validation on the streets. He started his own gang activity at 12, and by 13 he was smoking weed, drinking, breaking into cars, beating people up, and packing little pistols in his waistband. He began running with the Hoover Criminals, a major offshoot of the Crips that dominated his neighborhood.

Then he went to prison, a detour that turned his life around and may well have saved it.

Fields is not a scientist today, but he does have a rewarding union job as an electrical lineman. He works hard hours for good pay, and hes saving money to buy some rental properties. Hes married to an award-winning high school English teacher. They have a four-year-old son.

He is also a committed Christian. He now carries his Bible with him in his truck at work. You shall not murder, says his New King James Version of the Bible. He always knew that deadly violence was wrong. But in the world he saw around him, it was kill or be killed.

I always believed in God, even when I was young, he says. But as a teenager he told himself that he was fighting thugs and acting in self-defense. Its no secret that you can convince yourself that anything you are doing is correct, he notes.

The safe city

While murder rates fell nationally, in New York City they fell further faster and continued to drop longer. From 1990 to 2009, notes Franklin Zimring, a criminologist and University of California Berkeley law professor, murder rates in NYC dropped 82 percent. The next nine largest cities saw a 56 percent drop. Something different happened in New York that went beyond the national decline.

The demographics and socioeconomic status of New Yorkers remained largely unchanged over this period, Zimring argues, meaning that sociological explanations cannot explain the difference. And during an 18-year period in which national incarceration rates climbed by 65 percent, New Yorks rate fell by 28 percent. So they werent fighting crime by locking people up for longer terms.

What accounts for the difference? Zimring points to innovations in police work. It started in 1990, when the city added 7,000 new cops on the beat. It continued with database-driven focus on hotspots and aggressive (and controversial) tactics on the street, including stop and frisk. Crucially, Zimring argues, New York police set out to shut down open drug markets, cutting into the violence associated with turf battles.

While some dispute Zimrings data and explanations on the margins, there is little question that something dramatic happened in New York, that it involved effective police work, and that demographic changes such as gentrification played little if any role.

The core insight from Zimrings New York study is that crime is not purely sociologically determined. Streets can be made safer without waiting for generational social surgery. Those who argued that you have to attack root causes to measurably reduce crime were wrong, Zimring says.

Neighborhoods and families

Of course, those who focus on root causes rather than police work are not so much disputing Zimring as doing a very different kind of work.

From 1995 to 2002, Harvard sociologist Robert Sampson headed a team that surveyed nearly 3,000 Chicago youth about violent behavior, including fights and weapons carrying. They focused on these lower level violence precursors because surveying kids about homicide was, of course, a nonstarter.

Sampsons team overlaid that youth survey on a deeper survey of nearly 9,000 Chicago residents, broken down by actual housing units into neighborhoods. The result was extremely fine-grained data.

The study looked at personal factors, such as IQ and impulsivity; demographic factors, such as family status and education; and neighborhood factors. The study produced some surprising answers about which factors shape youth violence.

Sampsons least surprising result was that violence concentrates heavily in a small number of neighborhoods with extreme poverty and low education levels. Nor was he surprised to see that bad neighborhoods drag down solid families and good kids like Will Fields.

There is something about the neighborhood effect that is not just about the socio-economic status of the parents, Sampson said in an interview. Its not just what goes on underneath the roof.

But he also found that if parents were married, violence was lower, whether or not both parents were in the home. Cohabitation of biological parents did not have the same effect.

Most surprisingly, Sampson found that both children of immigrants and non-immigrant youth in immigrant-heavy neighborhoods were much less violent. Why do immigrants do better? Were still looking into that and no one knows for sure, Sampson said. But part of it is that those who choose to migrate to the United States often possess the very characteristics that lead to lower crime.

Moral cynicism

Sampsons research also focused on legal and moral cynicism, or a sense in a neighborhood of living outside the law, mistrustful of government, of the police, of one another. Its a corrosive disassociation from legal and moral norms.

Its a puzzle that all starts to fit together, Sampson said. You have communities over time that are poor, segregated, with few institutional resources, and the residents become, not surprisingly, they become cynical, they distrust each other, they distrust the police, and it feeds on itself.

In digging at the roots, Sampson is probing a complex array of social and familial problems. Possible alternatives include dispersing the next generation of at-risk youth into less poor and less segregated neighborhoods with stronger social fabric, rather than merely busing kids to nicer schools.

The off switch

All of Sampsons risk factors dogged Will Fields, raised by a single mom amidst extreme poverty in a segregated neighborhood rife with legal and moral cynicism.

When he arrived at prison, he initially came out fighting, looking to represent his gang on the inside. He got in trouble brawling and spent time in solitary confinement. Before long, the other guys took him aside. Its not like that here, they said.

They had turned off the gangster switch, he says.

This dumbfounded him. Fields today is an intense character, with measured words and a serious face. Being a gangster was not a game for him. In prison he saw through the fraud, saw the impotence around him for what it was, and began to plan a different life. He rediscovered his own faith and began reading the Bible again. Prison pulled Fields out of the neighborhood and gave him space and time to figure things out. He went in an angry kid, but he came out a reflective man.

Advice to a son

Two weeks after he left prison in 2007, Fields sat down with Renford Reese, a political science professor at Cal Poly Pomona. At the end of the interview, Reese asked, What would you tell your son if you had one today?

I would say, 'Dont lose your humanness,' Fields said. Its OK to have pride in your race, but dont forget that we are all human. Listen to the inner voice inside yourself that tells you right from wrong. You know when someone is telling you something thats not right. You know when someone is telling you something good, even though you may not want to hear it.

Avoid fantasies you get from movies and entertainment, he continued, speaking to his future son. Steer clear of the stereotypes people try to fit you into. Sometimes, cut the music off. Chill in silence. Reflect on where your life is going. Be serious about life.

Fields' son is now 4, still too young to grasp his dads words. But already, he has a far more promising future.

As a boy, Will Fields wanted to be a scientist. He had a chemistry set, a telescope and a microscope with slides, and for Christmas he once asked for math flash cards. He went to school at Brentwood Science Magnet School near Beverly Hills.

But, he didnt live there. Each morning he took a bus from his home in South Central Los Angeles up Interstate 405, past the airport, past Santa Monica and into the Brentwood hills. Each afternoon he went home to his neighborhood of run down streets, crack addicts on the corners, homes without fathers, communities without jobs and gang warfare everywhere.

You start to realize your place in life, Fields says. You see that youre at the bottom of the barrel. This your lot. This is going to be your life. As a child its frightening to see that reality.

And so the tide pulled him along. As Fields grew older, he got kicked out of multiple high schools for fighting. Then he was doing strong-arm robbery and battling other gangs for respect. Arrested when he was 19, he pled guilty to three counts of attempted murder. He spent the next six years in prison.

Fields came of age in a dangerous time and place. When he was born in 1981, the U.S. homicide rate had doubled to 10.2 per 100,000 from 4.6 in 1963. Through his boyhood, murder rates stayed high dipping to 7.9 in 1984, surging to 9.8 in 1991, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

But the national murder rate misses the crux of the story. Homicide in America disproportionally involves young African-American males, both as victims and offenders, and the disparity is enormous. From 1980 to 2008, victimization rates for blacks were six times higher than for whites. Offending rates were eight times higher.

In 1993, the year Fields turned 12 and began running with a gang, the murder victimization rate for black males between 18 and 24 years old stood at a whopping 196 per 100,000 compared to 19 per 100,000 for white men of the same age.

Then, to everyones surprise, murder rates tumbled, falling from 9.5 per 100,000 in 1993 to 5.5 in 2000. While most people blame crack cocaine for the spike during Will Fields boyhood, no one is totally sure why violence fell so sharply during his teens.

As the nation has taken stock of how the commandment to not kill is reflected in modern law and society, researchers have struggled to understand why homicide rates remain so high among impoverished urban black youth. Answers remain elusive, but two recent large studies offer some intriguing suggestions. A New York City study considers how effective police work can temper street violence. The other, based in Chicago, focuses on the role of poverty, neighborhoods and family structure in shaping or mitigating it.

Kill or be killed

For Will Fields, the disconnect between his tony school and his squalid streets and home life wore him down. Mocked by friends for using big words, he got no encouragement for his academic hopes. He rarely saw his father. His mother struggled to raise two boys, who as they grew became too much for her to handle.

In the end, he found validation on the streets. He started his own gang activity at 12, and by 13 he was smoking weed, drinking, breaking into cars, beating people up, and packing little pistols in his waistband. He began running with the Hoover Criminals, a major offshoot of the Crips that dominated his neighborhood.

Then he went to prison, a detour that turned his life around and may well have saved it.

Fields is not a scientist today, but he does have a rewarding union job as an electrical lineman. He works hard hours for good pay, and hes saving money to buy some rental properties. Hes married to an award-winning high school English teacher. They have a four-year-old son.

He is also a committed Christian. He now carries his Bible with him in his truck at work. You shall not murder, says his New King James Version of the Bible. He always knew that deadly violence was wrong. But in the world he saw around him, it was kill or be killed.

I always believed in God, even when I was young, he says. But as a teenager he told himself that he was fighting thugs and acting in self-defense. Its no secret that you can convince yourself that anything you are doing is correct, he notes.

The safe city

While murder rates fell nationally, in New York City they fell further faster and continued to drop longer. From 1990 to 2009, notes Franklin Zimring, a criminologist and University of California Berkeley law professor, murder rates in NYC dropped 82 percent. The next nine largest cities saw a 56 percent drop. Something different happened in New York that went beyond the national decline.

The demographics and socioeconomic status of New Yorkers remained largely unchanged over this period, Zimring argues, meaning that sociological explanations cannot explain the difference. And during an 18-year period in which national incarceration rates climbed by 65 percent, New Yorks rate fell by 28 percent. So they werent fighting crime by locking people up for longer terms.

What accounts for the difference? Zimring points to innovations in police work. It started in 1990, when the city added 7,000 new cops on the beat. It continued with database-driven focus on hotspots and aggressive (and controversial) tactics on the street, including stop and frisk. Crucially, Zimring argues, New York police set out to shut down open drug markets, cutting into the violence associated with turf battles.

While some dispute Zimrings data and explanations on the margins, there is little question that something dramatic happened in New York, that it involved effective police work, and that demographic changes such as gentrification played little if any role.

The core insight from Zimrings New York study is that crime is not purely sociologically determined. Streets can be made safer without waiting for generational social surgery. Those who argued that you have to attack root causes to measurably reduce crime were wrong, Zimring says.

Neighborhoods and families

Of course, those who focus on root causes rather than police work are not so much disputing Zimring as doing a very different kind of work.

From 1995 to 2002, Harvard sociologist Robert Sampson headed a team that surveyed nearly 3,000 Chicago youth about violent behavior, including fights and weapons carrying. They focused on these lower level violence precursors because surveying kids about homicide was, of course, a nonstarter.

Sampsons team overlaid that youth survey on a deeper survey of nearly 9,000 Chicago residents, broken down by actual housing units into neighborhoods. The result was extremely fine-grained data.

The study looked at personal factors, such as IQ and impulsivity; demographic factors, such as family status and education; and neighborhood factors. The study produced some surprising answers about which factors shape youth violence.

Sampsons least surprising result was that violence concentrates heavily in a small number of neighborhoods with extreme poverty and low education levels. Nor was he surprised to see that bad neighborhoods drag down solid families and good kids like Will Fields.

There is something about the neighborhood effect that is not just about the socio-economic status of the parents, Sampson said in an interview. Its not just what goes on underneath the roof.

But he also found that if parents were married, violence was lower, whether or not both parents were in the home. Cohabitation of biological parents did not have the same effect.

Most surprisingly, Sampson found that both children of immigrants and non-immigrant youth in immigrant-heavy neighborhoods were much less violent. Why do immigrants do better? Were still looking into that and no one knows for sure, Sampson said. But part of it is that those who choose to migrate to the United States often possess the very characteristics that lead to lower crime.

Moral cynicism

Sampsons research also focused on legal and moral cynicism, or a sense in a neighborhood of living outside the law, mistrustful of government, of the police, of one another. Its a corrosive disassociation from legal and moral norms.

Its a puzzle that all starts to fit together, Sampson said. You have communities over time that are poor, segregated, with few institutional resources, and the residents become, not surprisingly, they become cynical, they distrust each other, they distrust the police, and it feeds on itself.

In digging at the roots, Sampson is probing a complex array of social and familial problems. Possible alternatives include dispersing the next generation of at-risk youth into less poor and less segregated neighborhoods with stronger social fabric, rather than merely busing kids to nicer schools.

The off switch

All of Sampsons risk factors dogged Will Fields, raised by a single mom amidst extreme poverty in a segregated neighborhood rife with legal and moral cynicism.

When he arrived at prison, he initially came out fighting, looking to represent his gang on the inside. He got in trouble brawling and spent time in solitary confinement. Before long, the other guys took him aside. Its not like that here, they said.

They had turned off the gangster switch, he says.

This dumbfounded him. Fields today is an intense character, with measured words and a serious face. Being a gangster was not a game for him. In prison he saw through the fraud, saw the impotence around him for what it was, and began to plan a different life. He rediscovered his own faith and began reading the Bible again. Prison pulled Fields out of the neighborhood and gave him space and time to figure things out. He went in an angry kid, but he came out a reflective man.

Advice to a son

Two weeks after he left prison in 2007, Fields sat down with Renford Reese, a political science professor at Cal Poly Pomona. At the end of the interview, Reese asked, What would you tell your son if you had one today?

I would say, 'Dont lose your humanness,' Fields said. Its OK to have pride in your race, but dont forget that we are all human. Listen to the inner voice inside yourself that tells you right from wrong. You know when someone is telling you something thats not right. You know when someone is telling you something good, even though you may not want to hear it.

Avoid fantasies you get from movies and entertainment, he continued, speaking to his future son. Steer clear of the stereotypes people try to fit you into. Sometimes, cut the music off. Chill in silence. Reflect on where your life is going. Be serious about life.

Fields' son is now 4, still too young to grasp his dads words. But already, he has a far more promising future.