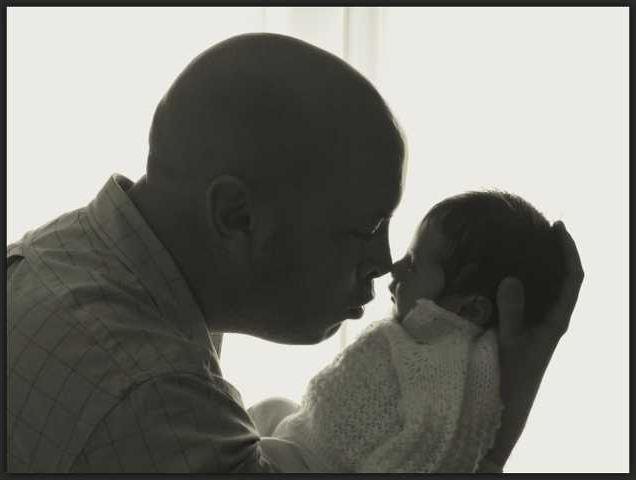

When Cheyenne, Wyoming, resident Michael Pea signed up for free welding lessons through a federally funded training program for low-income fathers, it surprised him that the first week of class seemed like a college psychology lecture, according to Marketplace.

Course instructor Chuck Skinner "trained on a big paper chart," the Marketplace article indicated. Scribbled on the chart were horizontal lines. The words "gratitude," create" and "chose" took up the paper's top half, while red letters toward the bottom spelled "anger," "fear" and "pain."

We can call them life shocks, Skinner said before transitioning into an overview of psychoanalysis, according to Marketplace. They are just going to happen.

Miles Bryan of Marketplace reported Pea bounced from job to job causing trouble and faced even more hurdles after getting custody of his 5-year-old nephew. Pea signed up for the fatherhood program, Dads Making a Difference, with hopes of job training, but the most important things he received were lessons on how to handle emotions and deal with crying children.

And Bryan noted that's a common story for participants of government-funded fatherhood initiatives: They arrive seeking solutions to issues like financial binds but leave the courses knowing "the softer stuff" that proves just as vital to long-term stability in the home.

Through Dads Making a Difference, Pea turned his life around, graduating from the course and landing a welding job to support his nephew.

I wont be upset or upset with myself because I can now provide for him, Pea said.

According to Marketplace, he wasn't the only one.

"Nine out of 10 in the Cheyenne program found jobs after graduating in the last few years, and most saw their wages go up by more than 50 percent," Bryan wrote.

According to MassLive, President Barack Obama put more than $500 million toward fatherhood classes in the U.S.

The 16-session courses walk participants through a wide range of topics including the five developmental stages of childhood and treating mothers with respect, Eli Saslow wrote for The Washington Post.

So, who utilizes these programs, and do success stories nationwide make them worth the price tag?

Research gathered by Family Studies indicated policymakers targeted "diverse, lower-income families."

According to Family Studies, fatherhood grantees included 341,000 participants in the first five years, each grantee assisting about 700 participants a year. Of those served, 40 percent were black, 30 percent white and 20 percent Hispanic/Latino.

Among Family Studies' interesting findings was this: Females constituted 16 percent of the participants.

"Twenty-two programs provided curriculum that combined fathering education with healthy relationship education, and four other programs focused solely on couple relationship education," according to Family Studies. "Also, a few organizations served women in unique situations, such as when the childs father was incarcerated or when women wanted to improve their relationship or work more effectively with the childs absent father."

The Family Studies piece stated evaluation of the programs effectiveness is limited with a number of rigorous studies in the works.

However, some reports included testimonials, participants describing life-changing skills developed through the curriculum, Family Studies reported.

If asked what the (fatherhood) program meant to me, I would say it helped me realize how much I really hurt and embarrassed my children by being a criminal and coming to prison, one man said of the initiative, according to Family Studies.

Ron Chimelis of MassLive wrote its unlikely the program will achieve a 100 percent success rating or anything close, for that matter.

Still, the ways these initiatives potentially benefit U.S. families make their cause something to support, Chimelis reported.

It may be having some positive impact, he wrote. I hope so. We should all hope so.

Latest causes stories:

#BlackLivesMatter's new campaign to end racist policing practices misses poverty factor, writer says

Today's grandparents are smarter than in years past, but poverty puts their health at risk

Poet spends $500K grant on vacation for others

Course instructor Chuck Skinner "trained on a big paper chart," the Marketplace article indicated. Scribbled on the chart were horizontal lines. The words "gratitude," create" and "chose" took up the paper's top half, while red letters toward the bottom spelled "anger," "fear" and "pain."

We can call them life shocks, Skinner said before transitioning into an overview of psychoanalysis, according to Marketplace. They are just going to happen.

Miles Bryan of Marketplace reported Pea bounced from job to job causing trouble and faced even more hurdles after getting custody of his 5-year-old nephew. Pea signed up for the fatherhood program, Dads Making a Difference, with hopes of job training, but the most important things he received were lessons on how to handle emotions and deal with crying children.

And Bryan noted that's a common story for participants of government-funded fatherhood initiatives: They arrive seeking solutions to issues like financial binds but leave the courses knowing "the softer stuff" that proves just as vital to long-term stability in the home.

Through Dads Making a Difference, Pea turned his life around, graduating from the course and landing a welding job to support his nephew.

I wont be upset or upset with myself because I can now provide for him, Pea said.

According to Marketplace, he wasn't the only one.

"Nine out of 10 in the Cheyenne program found jobs after graduating in the last few years, and most saw their wages go up by more than 50 percent," Bryan wrote.

According to MassLive, President Barack Obama put more than $500 million toward fatherhood classes in the U.S.

The 16-session courses walk participants through a wide range of topics including the five developmental stages of childhood and treating mothers with respect, Eli Saslow wrote for The Washington Post.

So, who utilizes these programs, and do success stories nationwide make them worth the price tag?

Research gathered by Family Studies indicated policymakers targeted "diverse, lower-income families."

According to Family Studies, fatherhood grantees included 341,000 participants in the first five years, each grantee assisting about 700 participants a year. Of those served, 40 percent were black, 30 percent white and 20 percent Hispanic/Latino.

Among Family Studies' interesting findings was this: Females constituted 16 percent of the participants.

"Twenty-two programs provided curriculum that combined fathering education with healthy relationship education, and four other programs focused solely on couple relationship education," according to Family Studies. "Also, a few organizations served women in unique situations, such as when the childs father was incarcerated or when women wanted to improve their relationship or work more effectively with the childs absent father."

The Family Studies piece stated evaluation of the programs effectiveness is limited with a number of rigorous studies in the works.

However, some reports included testimonials, participants describing life-changing skills developed through the curriculum, Family Studies reported.

If asked what the (fatherhood) program meant to me, I would say it helped me realize how much I really hurt and embarrassed my children by being a criminal and coming to prison, one man said of the initiative, according to Family Studies.

Ron Chimelis of MassLive wrote its unlikely the program will achieve a 100 percent success rating or anything close, for that matter.

Still, the ways these initiatives potentially benefit U.S. families make their cause something to support, Chimelis reported.

It may be having some positive impact, he wrote. I hope so. We should all hope so.

Latest causes stories:

#BlackLivesMatter's new campaign to end racist policing practices misses poverty factor, writer says

Today's grandparents are smarter than in years past, but poverty puts their health at risk

Poet spends $500K grant on vacation for others