The muzzle of a rifle peeks out from between two feet in Iranian-born artist Shirin Neshat's 1994 print "Allegiance with Wakefulness." Script covering the arches, balls and heels of both feet at first evokes Quranic verses, but the work a version of which Christie's sold for more than $110,000 in 2009 in fact quotes from the poetry of Iranian writer Tahereh Saffarzadeh, who died in 2008.

The photo is part of Neshat's "Women of Allah" series that she created between 1993 and 1997 after returning to Iran for the first time since she was marooned as a student in the United States during the 1979 Iranian Revolution. In the series and its "melancholic beauty," Neshat aims to show how "faith overcomes anxiety while martyrdom and self-sacrifice give the soul strength," she writes in the catalog to her current solo show at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden on the National Mall in Washington.

She adds that the women in the series are "strong and imposing" as they wear veils, "despite the Western representation of the veil as a symbol of Muslim women's oppression."

The Hirshhorn exhibit could be said to be a sort of rising for Neshat herself, and indeed for women artists from the Arab world more broadly, whose work debunks Western stereotypes and creates a new understanding of the role and life of women in Arab culture. The Hirshhorn is one of several major museums across the country to be exhibiting or have in the recent past shown the work of Arab women artists.

Theres noticeable attention to art from the Arab world in the United States, which is fantastic considering there was a time when it was a very rare occurrence, says Hrag Vartanian, editor-in-chief and co-founder of the art blogazine Hyperallergic.

European galleries and museums have shown artists from the Arab-speaking world, including women, for decades, but it was only after terrorists attack of Sept. 11, 2001, that the U.S. art world realized that there werent enough curators, researchers and writers studying art from the Arab world, according to Vartanian.

They decided to catch up though it took a good decade before we saw the fruits of this new interest, he says.

Deconstructing the veil

A 2010 photographic series titled "Mother, Daughter, Doll" by Yemeni-born artist Boushra Almutawakel, which is part of the "She Who Tells a Story" exhibit, like Neshat's art, questions Western views of the hijab as a kind of misogynistic prison.

The series opens with a mother wearing a headscarf posing with her arm around her young daughter, who sits on her lap holding a bald doll. (The doll's lack of hair will become particularly ironic when it gets a headscarf.) As the series unfolds, mother's and daughter's clothes become increasingly dark and more and more of their bodies are covered up. By the eighth and penultimate work in the series, only the eyes of mother, daughter and doll are visible; even their hands are covered by gloves. The ninth image has even lost the three figures.

One interpretation of the series could hinge on the absurdity of considering a doll so potentially erotic that it needs to be censored, or on the implications of requiring such a young girl to be literally covered from head to toe.

But the artist drew inspiration from Egyptian feminist writer Nawal El Saadawi, who "drew a parallel between women who wear the hijab (headscarf) or niqab (full Islamic veil with a slit for the eyes) and women who wear makeup," according to the exhibit catalog.

Almutawakel borrowed from El Saadawi's view that "both practices concealed women's identities" and challenges "the Western association of the veil with the oppression and ignorance of Middle Eastern women," the catalog adds.

Even further underscoring that point, another work of Almutawakel's shows a women veiled with an American flag.

That a cursory examination of Neshat's and Almutawakel's works may lead some American viewers down the wrong interpretive path of denouncing rather than seeing the potential of hijabs points to prevalent stereotypes that require interrogation in museum and gallery spaces.

I think many visitors would be surprised at the level of freedom, education, politics and intellectual activity that Arab women have access to, says Marika Sardar, associate curator of South Asian and Islamic art at the San Diego Museum of Art. Seeing the works of art that they are capable of creating, as well as the level of theoretical sophistication with which they approach their artmaking, is extremely important.

Empathy through art

Although she believes that U.S. galleries and museums are in fact responding to a heightened sensitivity about the Arab world in the context of civil strife and proxy wars following the Arab Spring, Amy Landau, associate curator of Islamic and south Asian art at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, sees things a little differently.

One cannot essentialize gender experience in such a broad expanse of geography, she says. Situations change from community to community.

But Landau warns that images, however powerful, can be misconstrued if the exhibits aren't properly contextualized, and not every woman artist from the Arab world is necessarily interested in, or impacted by, gender issues.

The most effective way to address misconceptions is through discussion, she says.

In the arts, as well as many other areas, women were significant participants in the dramatic transformations of the Arab Spring, says Diane Apostolos-Cappadona, a professor of religious art and cultural history in Georgetown Universitys Catholic studies and womens and gender studies programs and author of many books, including Encyclopedia of Women in Religious Art.

While some of the exhibits focusing on Arab women artists are clearly in response to a growing Western interest in the art of women and of the Arab world since the tragedy of 9/11, the trend began with a 1989 exhibit Contemporary Art from the Islamic World at the Barbican gallery in London, says Apostolos-Cappadona. That exhibit, featuring works from the Jordan National Art Gallery in Amman, highlighted the new position of Islamic women artists and curators, she says.

U.S. museum visitors, who may not be intimately familiar with the Arab world and its gender dynamics, stand to gain a new understanding from viewing works by Arab women artists. The same would go for works by artists in any region that viewers don't know well. But there is a particular need within the Arab world for outsiders to see "beyond news headlines and night-vision photographs," says Sarah Hassan, a New York writer who covers the arts for Harpers Bazaar Arabia, Reorient magazine, and others.

Hassan notes that Arab women artists often face censorship, exile or even execution. Neshat, for example, has said that she is not welcome back in Iran and hasn't visited since 1996, fearing for her safety.

Vartanian, of Hyperallergic, adds that contemporary art "can do wonderful things to break down stereotypes while exposing people to new perspectives." American viewers often see Arab women as "oppressed and marginalized," and works like Neshat's and Almutawakel's can dispel those stereotypes.

More work to do

Despite increased exposure of Arab women artists at U.S. museums and galleries, there remains a noticeable lack of response to this shift in art history departments at major colleges and universities throughout the country, according to Vartanian.

Many still dont have professors teaching non-Western art history, and particularly art from the so-called Arab world, he says.

Another hurdle to overcome to show works like Neshat's at the Hirshhorn has been U.S. curators' tendency for most of the 20th century to view Middle Eastern art created after 1800 as so derivative of European and American influence that it didn't merit exhibition. That's according to the San Diego Museum of Art's Sardar.

Today, curators and art historians have turned that thinking on its head, she says. They understand artists from Asia, Africa or the Middle East to be equal participants in the global contemporary art scene, driving new trends and new thinking as much as artists from Europe and America, and not simply imitating them.

And then there are the titles of the exhibits themselves, which can be full of their own stereotypes.

Institutions often rely on the familiar to pique the interest of audiences who will be interested in veils, crescents, hidden worlds and the other Orientalist fodder, Vartanian says. I'm going to guess this will change within a generation, when we can expect the art public to have a broader understanding of the artists, communities and issues involved.

The day after Vartanian shared his views, he followed up with an email, forwarding a press release for an exhibit coming up at the Worcester Art Museum. Its title? "Veiled Aleppo."

"You were asking about the word 'veiled?'" he wrote. "LOL."

--------------------------------------------------------------------

Current and past art exhibitions of works by female Arab artists:

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden on the National Mall in Washington is showing "Shiran Nassat: Facing History," photos and videos that examine the "nuances of power and identity in the Islamic world."

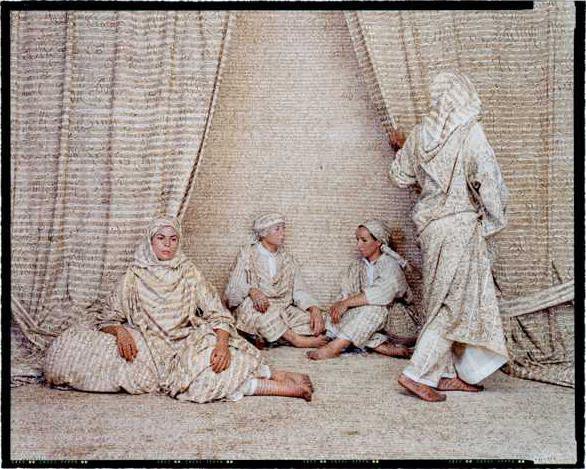

San Diego Museum of Art recently showed Moroccan-born Lalla Essaydi's photos, exploring "issues surrounding the role of women in Arab culture and their representation in the western European artistic tradition."

Pittsburghs Carnegie Museum of Art is exhibiting She Who Tells a Story: Women Photographers from Iran and the Arab World, which originated at Bostons Museum of Fine Arts and also hung at Stanford University, that "challenge stereotypes and provide insight into political and social issues."

Howard Greenberg Gallery (N.Y.) showed The Middle East Revealed: A Female Perspective (2014); Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Conn., exhibited Fluidity, Layering, Veiling: Perspectives from South Asian and Middle Eastern Women Artists (2011); and from 2008 to 2011, Breaking the Veils: Women Artists from the Islamic World traveled across the country, including to the Clinton Presidential Library, Yale University and Kennedy Center.

The photo is part of Neshat's "Women of Allah" series that she created between 1993 and 1997 after returning to Iran for the first time since she was marooned as a student in the United States during the 1979 Iranian Revolution. In the series and its "melancholic beauty," Neshat aims to show how "faith overcomes anxiety while martyrdom and self-sacrifice give the soul strength," she writes in the catalog to her current solo show at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden on the National Mall in Washington.

She adds that the women in the series are "strong and imposing" as they wear veils, "despite the Western representation of the veil as a symbol of Muslim women's oppression."

The Hirshhorn exhibit could be said to be a sort of rising for Neshat herself, and indeed for women artists from the Arab world more broadly, whose work debunks Western stereotypes and creates a new understanding of the role and life of women in Arab culture. The Hirshhorn is one of several major museums across the country to be exhibiting or have in the recent past shown the work of Arab women artists.

Theres noticeable attention to art from the Arab world in the United States, which is fantastic considering there was a time when it was a very rare occurrence, says Hrag Vartanian, editor-in-chief and co-founder of the art blogazine Hyperallergic.

European galleries and museums have shown artists from the Arab-speaking world, including women, for decades, but it was only after terrorists attack of Sept. 11, 2001, that the U.S. art world realized that there werent enough curators, researchers and writers studying art from the Arab world, according to Vartanian.

They decided to catch up though it took a good decade before we saw the fruits of this new interest, he says.

Deconstructing the veil

A 2010 photographic series titled "Mother, Daughter, Doll" by Yemeni-born artist Boushra Almutawakel, which is part of the "She Who Tells a Story" exhibit, like Neshat's art, questions Western views of the hijab as a kind of misogynistic prison.

The series opens with a mother wearing a headscarf posing with her arm around her young daughter, who sits on her lap holding a bald doll. (The doll's lack of hair will become particularly ironic when it gets a headscarf.) As the series unfolds, mother's and daughter's clothes become increasingly dark and more and more of their bodies are covered up. By the eighth and penultimate work in the series, only the eyes of mother, daughter and doll are visible; even their hands are covered by gloves. The ninth image has even lost the three figures.

One interpretation of the series could hinge on the absurdity of considering a doll so potentially erotic that it needs to be censored, or on the implications of requiring such a young girl to be literally covered from head to toe.

But the artist drew inspiration from Egyptian feminist writer Nawal El Saadawi, who "drew a parallel between women who wear the hijab (headscarf) or niqab (full Islamic veil with a slit for the eyes) and women who wear makeup," according to the exhibit catalog.

Almutawakel borrowed from El Saadawi's view that "both practices concealed women's identities" and challenges "the Western association of the veil with the oppression and ignorance of Middle Eastern women," the catalog adds.

Even further underscoring that point, another work of Almutawakel's shows a women veiled with an American flag.

That a cursory examination of Neshat's and Almutawakel's works may lead some American viewers down the wrong interpretive path of denouncing rather than seeing the potential of hijabs points to prevalent stereotypes that require interrogation in museum and gallery spaces.

I think many visitors would be surprised at the level of freedom, education, politics and intellectual activity that Arab women have access to, says Marika Sardar, associate curator of South Asian and Islamic art at the San Diego Museum of Art. Seeing the works of art that they are capable of creating, as well as the level of theoretical sophistication with which they approach their artmaking, is extremely important.

Empathy through art

Although she believes that U.S. galleries and museums are in fact responding to a heightened sensitivity about the Arab world in the context of civil strife and proxy wars following the Arab Spring, Amy Landau, associate curator of Islamic and south Asian art at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, sees things a little differently.

One cannot essentialize gender experience in such a broad expanse of geography, she says. Situations change from community to community.

But Landau warns that images, however powerful, can be misconstrued if the exhibits aren't properly contextualized, and not every woman artist from the Arab world is necessarily interested in, or impacted by, gender issues.

The most effective way to address misconceptions is through discussion, she says.

In the arts, as well as many other areas, women were significant participants in the dramatic transformations of the Arab Spring, says Diane Apostolos-Cappadona, a professor of religious art and cultural history in Georgetown Universitys Catholic studies and womens and gender studies programs and author of many books, including Encyclopedia of Women in Religious Art.

While some of the exhibits focusing on Arab women artists are clearly in response to a growing Western interest in the art of women and of the Arab world since the tragedy of 9/11, the trend began with a 1989 exhibit Contemporary Art from the Islamic World at the Barbican gallery in London, says Apostolos-Cappadona. That exhibit, featuring works from the Jordan National Art Gallery in Amman, highlighted the new position of Islamic women artists and curators, she says.

U.S. museum visitors, who may not be intimately familiar with the Arab world and its gender dynamics, stand to gain a new understanding from viewing works by Arab women artists. The same would go for works by artists in any region that viewers don't know well. But there is a particular need within the Arab world for outsiders to see "beyond news headlines and night-vision photographs," says Sarah Hassan, a New York writer who covers the arts for Harpers Bazaar Arabia, Reorient magazine, and others.

Hassan notes that Arab women artists often face censorship, exile or even execution. Neshat, for example, has said that she is not welcome back in Iran and hasn't visited since 1996, fearing for her safety.

Vartanian, of Hyperallergic, adds that contemporary art "can do wonderful things to break down stereotypes while exposing people to new perspectives." American viewers often see Arab women as "oppressed and marginalized," and works like Neshat's and Almutawakel's can dispel those stereotypes.

More work to do

Despite increased exposure of Arab women artists at U.S. museums and galleries, there remains a noticeable lack of response to this shift in art history departments at major colleges and universities throughout the country, according to Vartanian.

Many still dont have professors teaching non-Western art history, and particularly art from the so-called Arab world, he says.

Another hurdle to overcome to show works like Neshat's at the Hirshhorn has been U.S. curators' tendency for most of the 20th century to view Middle Eastern art created after 1800 as so derivative of European and American influence that it didn't merit exhibition. That's according to the San Diego Museum of Art's Sardar.

Today, curators and art historians have turned that thinking on its head, she says. They understand artists from Asia, Africa or the Middle East to be equal participants in the global contemporary art scene, driving new trends and new thinking as much as artists from Europe and America, and not simply imitating them.

And then there are the titles of the exhibits themselves, which can be full of their own stereotypes.

Institutions often rely on the familiar to pique the interest of audiences who will be interested in veils, crescents, hidden worlds and the other Orientalist fodder, Vartanian says. I'm going to guess this will change within a generation, when we can expect the art public to have a broader understanding of the artists, communities and issues involved.

The day after Vartanian shared his views, he followed up with an email, forwarding a press release for an exhibit coming up at the Worcester Art Museum. Its title? "Veiled Aleppo."

"You were asking about the word 'veiled?'" he wrote. "LOL."

--------------------------------------------------------------------

Current and past art exhibitions of works by female Arab artists:

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden on the National Mall in Washington is showing "Shiran Nassat: Facing History," photos and videos that examine the "nuances of power and identity in the Islamic world."

San Diego Museum of Art recently showed Moroccan-born Lalla Essaydi's photos, exploring "issues surrounding the role of women in Arab culture and their representation in the western European artistic tradition."

Pittsburghs Carnegie Museum of Art is exhibiting She Who Tells a Story: Women Photographers from Iran and the Arab World, which originated at Bostons Museum of Fine Arts and also hung at Stanford University, that "challenge stereotypes and provide insight into political and social issues."

Howard Greenberg Gallery (N.Y.) showed The Middle East Revealed: A Female Perspective (2014); Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Conn., exhibited Fluidity, Layering, Veiling: Perspectives from South Asian and Middle Eastern Women Artists (2011); and from 2008 to 2011, Breaking the Veils: Women Artists from the Islamic World traveled across the country, including to the Clinton Presidential Library, Yale University and Kennedy Center.