Editor’s note: This is the first installment to an in-depth series on the opioid epidemic, focused on the impact to our local Liberty County community.

“I had a crush on a guy who was doing drugs and it didn’t take a month from being in that environment that I started using,” Kirsten Garner said.

20-year-old Garner recently moved from Glenville to Hinesville after battling with addiction for three years before getting clean. Her choice of drugs included methamphetamine, Xanax, and suboxone.

“I was speedballing and woke up on the side of the road,” Garner said. “My car was still in drive and there was a meth pipe and Xanax in my lap … it was one of my darkest moments.”

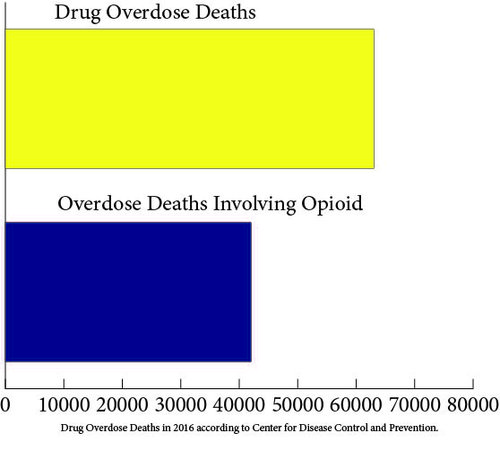

According to the Center for Disease Control, in 2016 there were more than 63,600 drug overdose dose deaths in the United States. More than half of these deaths involved a prescription or illicit opioids.

In Georgia there were 918 opioid- related deaths in 2016 that averaged a rate of 8.8 deaths per 100,000 persons according to drugabuse.gov.

According to the Opioid & Health Indicators Database, out of 159 counties in Georgia, Liberty County ranked 49 on the percent of people over the age of 12 who reported drug dependency in 2014.

Narcotic Investigator Richard Kunda of the Hinesville Police Department states that about a year ago the Hinesville Police Department began carrying Naloxone commonly known as Narcan, which is an FDA approved treatment to treat suspected opioid overdoses.

“[Hinesville] isn’t any different than anywhere else in America when it comes to opioids,” Kunda said.

According to the Georgia Bureau of Investigation’s Forensic Science sector, in Liberty County 22 drug samples sent to the crime lab for testing came back positive for opioids in 2016. In 2017, 33 drug samples sent for testing came back positive for opioids, with two samples testing positive for Fentanyl.

The rise of synthetic opioids like fentanyl is a driving factor in the increase of drug overdose deaths nationwide. It is estimated that over 42,000 deaths in 2016 can be attributed to opioid drug overdose, according to the CDC website.

Fentanyl can be 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine and 25 to 50 more potent than heroin, according to the United States Drug Enforcement Administration.

“Very little bit of fentanyl can kill you, and you don’t know if what drug you’re taking is laced with it,” said Atlantic Judicial Circuit Drug Court Administrator Glenda Harriman. “We have a variety of what are clients are addicted to, like meth, oxy, cocaine and spice … it’s too accessible.”

According to the CDC, 82.2 – 95 out of 100 people were prescribed opioids by Georgia doctors in 2012.

“I don’t think it’s surprising, we have doctors here that give prescriptions for pain like hydrocodone and people get addicted and it turns into a nightmare,” Harriman said.

“We have some using kratom which is a synthetic opioid that we have to test special for,” said Harriman.

There is a difference between the terms opiate and opioid, according to centeronaddiction.org. Opiates are derived from the poppy plant and are natural. Opioid is a modern term that can refer to both natural and synthesized narcotics. Opioids include: heroin, codeine, morphine, vicodin, fentanyl and methadone.

Maj. Jeffrey Hein of the Liberty County Sheriff’s Office said that the fight against drugs has to be waged from two sides.

“For us we have always had an aggressive approach to narcotics … we address the supply and go after users,” Hein said.

“What we are seeing now is people getting legitimate prescriptions and then selling them,” said Hein, “The street value for hydrocodone is a dollar a milligram.” That means if someone were to be prescribed a 30 day supply of 10 milligrams of hydrocodone taken twice a day, the entire bottle can have a street value of $600.

“Some people are looking at pills like they’re clean because it’s not coming out of someone’s garage, its coming from doctors,” Hein said.

In 2015, Liberty County was prescribed 430.4 milligrams of opioids per capita according to opioid.amfar.org.

“Just like in any other profession you have good doctors and bad doctors,” Hein said.

Manufacturers, distributors, and doctors have been at the forefront of conversation in the opioid abuse epidemic.

In 2018 more than 12 counties in Georgia including Chatham County sued opioid manufacturers and distributors according to court documents. The suit filed on March 6 in Chatham County, is the beginning of many lawsuits spanning across the country being filed.

“It’s the worst drug crises we have ever had in the United States,” said Attorney Mark Tate, who is representing Chatham County in its lawsuit.

Tate states that due to opiate companies expanding to create greater revenue, our cities, counties and other third parties have suffered great expense due to the increase in law enforcement costs, increase in costs for treating addiction, increased court costs, and increased jail costs.

“It’s a vast, vast set of damages to communities; the profits would not exist if we [taxpayers] were not here to clean the costs,” Tate said.

In Liberty County, District Attorney Tom Durden said the rise in opioid cases is not following trends he’s seen before with other drugs.

“A lot of times what you see when there’s an increase in one drug, there’s a decrease in another,” Durden said. “With [opioids], we aren’t seeing a significant decrease in other drugs.”

Along with the increase in opioid cases, Durden has also seen an increase in certain crimes.

“When we started seeing opioids, we saw an increase in forging prescriptions, theft, property crime and even violent crimes,” Durden said. “Where this is going, I don’t know … it’s similar to what you saw with the crack epidemic.”

Reporter Asha Gilbert will follow this installment with a piece focused on the medical community’s role in combating the opioid crisis.