In 2011, things were finally looking up for Robert Williams at least it seemed that way.

The 57-year-old welder from Houston had been working as a temporary employee with National Oilwell Varco, an oil and gas drilling company. One day, his supervisor pulled him aside and offered him a full-time position with regular hours and benefits. They were impressed with his work ethic and reliability. Hed need to fill out an application but was assured it was just a formality.

The application form Williams filled out contained some questions about candidates' criminal records. Determined to be honest, Williams disclosed that in 1978 he was convicted of armed robbery and spent 20 years in prison, which, incidentally, is where he learned to weld.

Williams assumed National Oilwell Varco already knew this because he shared it on his temp agency application. So he was shocked when he was told that not only he didnt get the full-time job, but that he was also no longer welcome as a temporary employee. A representative from HR told him the company had a policy of not hiring people with criminal records, no exceptions.

Williams is just one of about 70 million Americans, 1 in 4 adults, with a criminal record, according to the National Employment Law Project, a national organization advocating for employee rights. The likelihood of being invited to interview after turning in a job application is only about 34 percent, according to a 2003 study by Devah Pager, professor of sociology at Harvard University. Revealing a criminal history, she found, reduces those odds by 50 percent for white men and 64 percent for black men.

Early this summer, Oregon signed ban the box legislation into law, its solution for ensuring people with criminal records get a fair shot at jobs they are qualified for. Oregon's legislation prohibits employers from asking job candidates about their criminal history in the early stages of the application process. However, employers are allowed to run background checks before making a formal offers of employment.

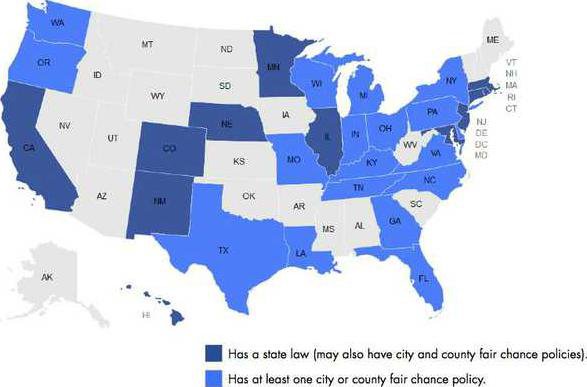

With this bill Oregon joins 17 states and over 100 cities to pass some form of ban the box legislation. While the particulars of the legislation vary between jurisdictions, proponents say eliminating the criminal history check box from job applications will reduce prejudice against those with records, improve their employment opportunities and reduce recidivism.

"These reforms restore hope and opportunity to qualified job-seekers with a criminal record who struggle against significant odds to find work and to give back to their communities," said Michelle Natividad Rodriguez, senior staff attorney with the National Employment Law Project.

While many support the idea of making it easier for people with criminal records to find work, ban the box legislation is not without its critics: Academics who say it simply delays prejudice, employment experts who worry about the unintended consequences and attorneys who say it opens employers up to litigation for employment discrimination.

Ban the box

Ban the box laws increase the number of people who find work in two ways, according to Johnathan Smith, assistant counsel with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. First, if employers consider an applicants skills and experience before seeing a criminal record, they will be more likely to consider hiring that person. Second, if people with criminal records know they will be evaluated on their skills and experience, and not automatically disqualified because of their history, they will be more likely to apply for jobs.

As more places adopt the laws, research is starting to pop up suggesting that ban the box works. The city of Durham, North Carolina, for example, saw a 590 percent increase in hires with criminal records between 2011 and 2014 after its "ban the box" legislation was enacted. In addition, it found that 96 percent of job applicants with criminal records who were recommended for hire prior to the record check ultimately got those jobs.

Employment history hurts

Lester Rosen, founder and CEO of Employment Screening Resources, a company that specializes in background checks, agrees something should be done to ensure that people with criminal records arent automatically disqualified for jobs. Still, he has doubts that ban the box legislation is the solution. Employers use criminal records as a way to quickly weed out job applicants. If they cant ask that question, they will look for other ways to get the information, Rosen said. The most likely alternative: employment history.

If an applicant has a documented employment history without significant interruptions, then an employer can have some degree of confidence that the person has probably not spent time in custody for a serious matter, Rosen said.

In short, employment history becomes a proxy for criminal record.

Ex-felons won't be the only ones hurt by this kind of policy shift, according to Rosen. It would mean anyone with gaps in their work history will be less likely to get a job interview: parents who put careers on hold to raise children; children who took time off work to care for elderly relatives; people whove had trouble maintaining a consistent employment record during a recession.

Delaying the inevitable

While ban the box laws are designed to encourage employers to keep an open mind when evaluating people with criminal records, there is no evidence that it actually leads to more hires, according to Eli Lehrer, president of R Street Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based libertarian think tank that advocates for free markets and limited government.

"If there were evidence to support 'ban the box' I would get behind it," said Lehrer. "But we are still waiting for that gold standard study. There's no proof it works."

In other words, success in Durham is not sufficient proof that this is a policy that works around the country.

But that isn't the only opposition to ban the box.

"The laws dont specify how employers should evaluate a candidates record once they find out about their record," said Stacy Hickox, associate professor of employment law at Michigan State University. "It is still at each employers discretion to determine what weight a criminal record carries."

That's problematic because employers aren't always going to be aware of the research that can help them properly assess the risk of hiring a person with a criminal record, Hickox said.

For example, "Most employers assume that hiring someone with a criminal record exposes them to greater risks," she said.

Research, however, contradicts the popular opinion.

"A person who committed an offense seven or more years ago, and has not committed any crimes since, is no more likely to commit an offense than a person with no record at all," she said.

In fairness some jurisdictions, such as San Francisco, attempt to provide employers with guidance on how to interpret a candidate's criminal record. However, they are the exception, not the norm. Without guidance on how to evaluate a criminal record, Hickox fears that ban the box legislation just delays discrimination: It kicks the can down the road, she said.

In some cases, like that of Williams, a potential employer may reject an application of someone despite having direct knowledge the person has the necessary skills and reliability to do the job.

Employer liability

Ban the box legislation may also be problematic if it opens employers up to negligent hiring lawsuits, according to Matthew V. DelDucaa, chair of the Labor and Employment Group at the law firm Pepper Hamilton.

Employers are responsible for the reasonably foreseeable actions of their employees," he said. "Even employers who want to give an applicant a second chance' have to evaluate the risk that the applicant will hurt someone by an act consistent with his past conviction."

Steve Suflas, a labor and employment attorney and partner in the Denver office of Ballard Spahr LLP, believes employers shouldnt lose sleep on lawsuits regarding negligent hiring. Discriminatory hiring practices, on the other hand, are a reality employers need to prepare for.

Theres been a huge increase since 2012 in suits alleging discriminatory hiring practices on the basis of criminal records, said Suflas.

To protect themselves from litigation, employers would have to go through a rigorous process to prove to the court that they did not reject a candidate solely on the basis of his or her criminal record, he said.

How rigorous is that process? New Jersey attorney Maxine Neuhauser suggests 18 steps employers should follow such as: giving the candidate 10 days to provide explanation of their record and providing rejected candidates with a written report detailing the reasons for not hiring them along with a list of the evidence and mitigating factors considered.

Rodriguez agrees that simply deleting a box from job application forms won't remove the barriers to employment people with criminal records face. Still, she believes it's a good place to start.

"We have a broken justice system that spans employment, housing and other important facets of life," Rodriguez said. "This is a simple procedural change that will lend itself to a broader set of hiring reforms."

The 57-year-old welder from Houston had been working as a temporary employee with National Oilwell Varco, an oil and gas drilling company. One day, his supervisor pulled him aside and offered him a full-time position with regular hours and benefits. They were impressed with his work ethic and reliability. Hed need to fill out an application but was assured it was just a formality.

The application form Williams filled out contained some questions about candidates' criminal records. Determined to be honest, Williams disclosed that in 1978 he was convicted of armed robbery and spent 20 years in prison, which, incidentally, is where he learned to weld.

Williams assumed National Oilwell Varco already knew this because he shared it on his temp agency application. So he was shocked when he was told that not only he didnt get the full-time job, but that he was also no longer welcome as a temporary employee. A representative from HR told him the company had a policy of not hiring people with criminal records, no exceptions.

Williams is just one of about 70 million Americans, 1 in 4 adults, with a criminal record, according to the National Employment Law Project, a national organization advocating for employee rights. The likelihood of being invited to interview after turning in a job application is only about 34 percent, according to a 2003 study by Devah Pager, professor of sociology at Harvard University. Revealing a criminal history, she found, reduces those odds by 50 percent for white men and 64 percent for black men.

Early this summer, Oregon signed ban the box legislation into law, its solution for ensuring people with criminal records get a fair shot at jobs they are qualified for. Oregon's legislation prohibits employers from asking job candidates about their criminal history in the early stages of the application process. However, employers are allowed to run background checks before making a formal offers of employment.

With this bill Oregon joins 17 states and over 100 cities to pass some form of ban the box legislation. While the particulars of the legislation vary between jurisdictions, proponents say eliminating the criminal history check box from job applications will reduce prejudice against those with records, improve their employment opportunities and reduce recidivism.

"These reforms restore hope and opportunity to qualified job-seekers with a criminal record who struggle against significant odds to find work and to give back to their communities," said Michelle Natividad Rodriguez, senior staff attorney with the National Employment Law Project.

While many support the idea of making it easier for people with criminal records to find work, ban the box legislation is not without its critics: Academics who say it simply delays prejudice, employment experts who worry about the unintended consequences and attorneys who say it opens employers up to litigation for employment discrimination.

Ban the box

Ban the box laws increase the number of people who find work in two ways, according to Johnathan Smith, assistant counsel with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. First, if employers consider an applicants skills and experience before seeing a criminal record, they will be more likely to consider hiring that person. Second, if people with criminal records know they will be evaluated on their skills and experience, and not automatically disqualified because of their history, they will be more likely to apply for jobs.

As more places adopt the laws, research is starting to pop up suggesting that ban the box works. The city of Durham, North Carolina, for example, saw a 590 percent increase in hires with criminal records between 2011 and 2014 after its "ban the box" legislation was enacted. In addition, it found that 96 percent of job applicants with criminal records who were recommended for hire prior to the record check ultimately got those jobs.

Employment history hurts

Lester Rosen, founder and CEO of Employment Screening Resources, a company that specializes in background checks, agrees something should be done to ensure that people with criminal records arent automatically disqualified for jobs. Still, he has doubts that ban the box legislation is the solution. Employers use criminal records as a way to quickly weed out job applicants. If they cant ask that question, they will look for other ways to get the information, Rosen said. The most likely alternative: employment history.

If an applicant has a documented employment history without significant interruptions, then an employer can have some degree of confidence that the person has probably not spent time in custody for a serious matter, Rosen said.

In short, employment history becomes a proxy for criminal record.

Ex-felons won't be the only ones hurt by this kind of policy shift, according to Rosen. It would mean anyone with gaps in their work history will be less likely to get a job interview: parents who put careers on hold to raise children; children who took time off work to care for elderly relatives; people whove had trouble maintaining a consistent employment record during a recession.

Delaying the inevitable

While ban the box laws are designed to encourage employers to keep an open mind when evaluating people with criminal records, there is no evidence that it actually leads to more hires, according to Eli Lehrer, president of R Street Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based libertarian think tank that advocates for free markets and limited government.

"If there were evidence to support 'ban the box' I would get behind it," said Lehrer. "But we are still waiting for that gold standard study. There's no proof it works."

In other words, success in Durham is not sufficient proof that this is a policy that works around the country.

But that isn't the only opposition to ban the box.

"The laws dont specify how employers should evaluate a candidates record once they find out about their record," said Stacy Hickox, associate professor of employment law at Michigan State University. "It is still at each employers discretion to determine what weight a criminal record carries."

That's problematic because employers aren't always going to be aware of the research that can help them properly assess the risk of hiring a person with a criminal record, Hickox said.

For example, "Most employers assume that hiring someone with a criminal record exposes them to greater risks," she said.

Research, however, contradicts the popular opinion.

"A person who committed an offense seven or more years ago, and has not committed any crimes since, is no more likely to commit an offense than a person with no record at all," she said.

In fairness some jurisdictions, such as San Francisco, attempt to provide employers with guidance on how to interpret a candidate's criminal record. However, they are the exception, not the norm. Without guidance on how to evaluate a criminal record, Hickox fears that ban the box legislation just delays discrimination: It kicks the can down the road, she said.

In some cases, like that of Williams, a potential employer may reject an application of someone despite having direct knowledge the person has the necessary skills and reliability to do the job.

Employer liability

Ban the box legislation may also be problematic if it opens employers up to negligent hiring lawsuits, according to Matthew V. DelDucaa, chair of the Labor and Employment Group at the law firm Pepper Hamilton.

Employers are responsible for the reasonably foreseeable actions of their employees," he said. "Even employers who want to give an applicant a second chance' have to evaluate the risk that the applicant will hurt someone by an act consistent with his past conviction."

Steve Suflas, a labor and employment attorney and partner in the Denver office of Ballard Spahr LLP, believes employers shouldnt lose sleep on lawsuits regarding negligent hiring. Discriminatory hiring practices, on the other hand, are a reality employers need to prepare for.

Theres been a huge increase since 2012 in suits alleging discriminatory hiring practices on the basis of criminal records, said Suflas.

To protect themselves from litigation, employers would have to go through a rigorous process to prove to the court that they did not reject a candidate solely on the basis of his or her criminal record, he said.

How rigorous is that process? New Jersey attorney Maxine Neuhauser suggests 18 steps employers should follow such as: giving the candidate 10 days to provide explanation of their record and providing rejected candidates with a written report detailing the reasons for not hiring them along with a list of the evidence and mitigating factors considered.

Rodriguez agrees that simply deleting a box from job application forms won't remove the barriers to employment people with criminal records face. Still, she believes it's a good place to start.

"We have a broken justice system that spans employment, housing and other important facets of life," Rodriguez said. "This is a simple procedural change that will lend itself to a broader set of hiring reforms."