Editor's note: This article is part of "The Ten Today," a series that examines the Ten Commandments in modern society. This story explores the third commandment: "Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord the God in vain."

When she's in a courtroom, Wendy Patrick, a deputy district attorney for San Diego, uses some of the roughest words in the English language. She has to, given that she prosecutes sex crimes.

Yet just repeating the words is a challenge for a woman who not only holds a law degree but also degrees in theology and is an ordained Baptist minister: "I have to say (a particularly vulgar expletive) in court when I'm quoting other people, usually the defendants," she admitted.

There's an important reason Patrick has to repeat vile language in court.

"My job is to prove a case, to prove that a crime occurred," she explained. "There's often an element of coercion, of threat, (and) of fear. Colorful language and context is very relevant to proving the kind of emotional persuasion, the menacing, a flavor of how scary these guys are. The jury has to be made aware of how bad the situation was. Those words are disgusting."

It's so bad, Patrick said, that on occasion a judge will ask her to tone things down, fearing a jury's emotions will be improperly swayed.

And yet Patrick continues to be surprised when she heads over to San Diego State University for her part-time work of teaching business ethics.

"My students have no qualms about dropping the 'F-bomb' in class," she said. "The culture in college campuses is that unless they're disruptive or violating the rules, that's (just) the way kids talk."

Experts say people swear for impact, but the widespread use of strong language may in fact lessen that impact, as well as lessen society's ability to set apart certain ideas and words as sacred. From Hollywood to Wall Street, whether "taking the Lord's name in vain" as proscribed in the Ten Commandments or employing other vulgarity, the words people use both shape and reflect modern culture in powerful ways.

"Expressing everything that is within you is a dangerous cultural idea," said Rabbi David Wolpe, spiritual leader of Los Angeles' Sinai Temple. "Discipline and restraint is as important to the shaping of personal character as is full expression."

A history of swearing

A ban against profaning God's name can trace its roots back to the "Noahide laws" attributed by Jewish historians to the post-flood patriarch. But the late 17th century saw the beginning of a rise in profane and vulgar language, according to historian Melissa Mohr, author of the 2013 book "Holy (Expletive): A Brief History of Swearing." In that book, Mohr asserts that the 18th and 19th centuries saw the mainstreaming of profanity in many parts of culture, including plays by George Bernard Shaw.

Mohr also quotes an 1887 issue of Liberty, a Boston-based magazine, which proclaimed, "We say that it is no worse to swear by the realities of nature as exemplified in the human body than to swear by a holy ghost. One is obscenity; the other profanity."

"Profanity is something that has become so widespread in its acceptance that it doesn't carry the weight that it did 20 or 30 years ago," Patrick, the prosecutor and professor, said.

Wolpe likewise asserts the widespread use of so-called swear words have lessened their impact: "Its purpose is to be shocking and powerful in speech at exceptional times," Wolpe explained. "Now that we've made it normal, even our profanity doesn't have the force that it should have."

The conservative Jewish cleric noted the overuse of God's name in casual ways signals "a loss to our society" of reverence and awe. (As an example, consider the now-conversational use of the texting abbreviation "OMG," for "Oh, My God," and how the full phrase often shows up in settings as benign as home-design shows without any recognition of its meaning by the speakers.)

"If nothing is considered sacred, then I guess the leveling reality of that is that everything is the same," Wolpe said. "There's nothing that people can treasure beyond the normal. You can't distinguish something as exceptional when everything is on the same level."

"People have been swearing for hundreds of years before there was television, radio," declared Tim Jay, a psychology professor at the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts and the author of "Why We Curse" and "Cursing in America."

"I don't think people learn how to swear from watching movies," Jay said. "In the surveys we've done, especially with people looking back at how they learned cursing, show that they learn from family, siblings and friends."

That said, Jay is willing to lay some blame at the feet of the media and technology: "We have a deeper cultural awareness of it because we are inundated with media. Television is on, news is on 24 hours a day; there was nothing like this in the 1930s. Everybody's got a phone or the Internet, so we reflect on these things."

An evolution

One area where Jay actively tracks the use of cursing is among the very young infants, toddlers and children. There, he says, the amount of cursing has remained constant over the past 30 years, which he and his wife Kristen, an assistant professor at Marist College in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., have confirmed in parallel studies.

"Between ages one and 12, we found progressive growth towards an adult vocabulary," Jay said. "Young kids, preschoolers, are focused on bodies, use 'poop,' and 'poophead,' which disappear as they get more adult-like language. We compared this with data in the 1980s, and overall, what we recorded 30 years ago is not a lot different than what we recorded a couple of years ago."

Does Jay believe cursing is a good thing for society? "I think, on an individual level, when you think of coping and venting, this is good for stress it's better than shooting or hitting each other," he said. "But, certainly, when you're looking at prejudice and bullying those aren't good."

Jay acknowledged some areas of society are clamping down: "Of course, we have laws that prohibit discrimination, harassment and threats," he said. "We have increased surveillance of workplace and school communications, (both) oral and written or electronic. Families who are religious uphold traditional standards; those less rigid probably have (more) relaxed standards."

The workplace is an area where experts are divided about the use of language. Jay said it's a way to let off steam and "build camaraderie."

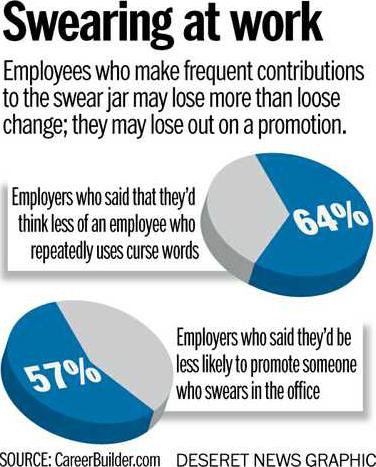

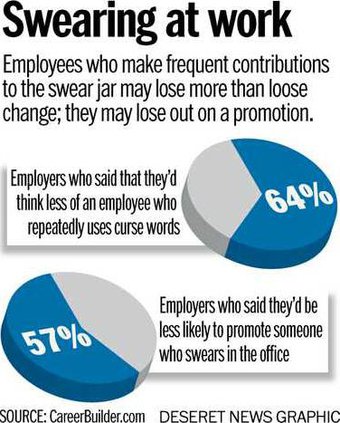

But Diane Gottsman, an etiquette expert in San Antonio, in a blog about workers cleaning up their language, cited a 2012 Career Builder survey in which 57 percent of employers say they wouldn't hire a candidate who used profanity. And while some entrepreneurs lay down a strict no-cussing rule for their workplaces, CNBC reported earlier this year, a financial market insider affirmed to the network that cursing is quite prevalent in that environment.

"Wall Street is a hotbed of profanity," Dennis Gibb, a former trader at Morgan Stanley and junior partner at Bear Stearns, told CNBC. "You've got a lot of high-testosterone people with big egos making a lot of money."

Gottsman partly concurred: "I can definitely see that the times have changed. And we are exposed far more than in the past, in the good old days. One of the reasons it hurts us in business is that we come across as not having command of our language. That's why it's very important to use our words for power, and we lose our power when we start substituting strong words with profanity."

She added, "It all comes down to respect: if you wouldn't say it to your grandmother, you shouldn't say it to your client, your boss, your girlfriend or your wife."

Is Hollywood to blame?

And what about Hollywood, which is often blamed for coarsening the language?

According to Barbara Nicolosi, a Hollywood script consultant and film professor at Azusa Pacific University, an evangelical Christian school, lazy script writing is part of the explanation for the blue tide on television and in the movies.

"There's never one reason for things," Nicolosi said. "The dramatist's job is to create emotion in the audience. The artful way, the skilled way, of creating emotion is by successfully making audiences connect with the emotions at play and escape through the characters."

By contrast, she said, "Bad writers go for the emotional punch of crass language," hence the fire-hose spray of obscenities some modern films, almost regardless of whether or not the subject demands it. Martin Scorsese's "The Wolf of Wall Street," about a fraudulent broker, is littered with obscenities and might well reflect the industry upon which it is based; others saw a brief, profanity-laden segment of "The King's Speech" as unnecessary.

Nicolosi, who noted that "nobody misses the bad language" when it's omitted from a script, said any change in the industry has to come from among its ranks: "Writers need to have a conversation among themselves and in the industry where we popularize much more responsible methods in storytelling," she said. "It has to be organic, and a creative movement from within."

That change can't come quickly enough for Melissa Henson, director of grass-roots education and advocacy for the Parents Television Council, a pro-decency group. While conceding there is a market for "adult-themed" films and language, Henson said it may be smaller than some in the industry want to admit.

"The volume of R-rated stuff that we're seeing probably far outpaces what the market would support," she said. By contrast, she added, "the rate of G-rated stuff is hardly sufficient to meet market demands."

To support her claim, Henson noted the research of groups such as Movieguide, a Christian organization that rates films' family friendliness, and which consistently finds that "a PG-13 movie outperforms an R-rated one, PG-rated movies outperform PG-13, and G-rated films outperform PG (ones)." One reason is simple, she said: a studio can "make more money selling tickets to a family than just two tickets to a couple going out for date night."

Henson believes arguments about an "artistic need" for profanity are disingenuous.

"You often hear people try to make the argument that art reflects life," Henson said. "I don't hold to that. More often than not, 'art' shapes the way we live our lives, and it skews our perceptions of the kind of life we're supposed live."

When she's in a courtroom, Wendy Patrick, a deputy district attorney for San Diego, uses some of the roughest words in the English language. She has to, given that she prosecutes sex crimes.

Yet just repeating the words is a challenge for a woman who not only holds a law degree but also degrees in theology and is an ordained Baptist minister: "I have to say (a particularly vulgar expletive) in court when I'm quoting other people, usually the defendants," she admitted.

There's an important reason Patrick has to repeat vile language in court.

"My job is to prove a case, to prove that a crime occurred," she explained. "There's often an element of coercion, of threat, (and) of fear. Colorful language and context is very relevant to proving the kind of emotional persuasion, the menacing, a flavor of how scary these guys are. The jury has to be made aware of how bad the situation was. Those words are disgusting."

It's so bad, Patrick said, that on occasion a judge will ask her to tone things down, fearing a jury's emotions will be improperly swayed.

And yet Patrick continues to be surprised when she heads over to San Diego State University for her part-time work of teaching business ethics.

"My students have no qualms about dropping the 'F-bomb' in class," she said. "The culture in college campuses is that unless they're disruptive or violating the rules, that's (just) the way kids talk."

Experts say people swear for impact, but the widespread use of strong language may in fact lessen that impact, as well as lessen society's ability to set apart certain ideas and words as sacred. From Hollywood to Wall Street, whether "taking the Lord's name in vain" as proscribed in the Ten Commandments or employing other vulgarity, the words people use both shape and reflect modern culture in powerful ways.

"Expressing everything that is within you is a dangerous cultural idea," said Rabbi David Wolpe, spiritual leader of Los Angeles' Sinai Temple. "Discipline and restraint is as important to the shaping of personal character as is full expression."

A history of swearing

A ban against profaning God's name can trace its roots back to the "Noahide laws" attributed by Jewish historians to the post-flood patriarch. But the late 17th century saw the beginning of a rise in profane and vulgar language, according to historian Melissa Mohr, author of the 2013 book "Holy (Expletive): A Brief History of Swearing." In that book, Mohr asserts that the 18th and 19th centuries saw the mainstreaming of profanity in many parts of culture, including plays by George Bernard Shaw.

Mohr also quotes an 1887 issue of Liberty, a Boston-based magazine, which proclaimed, "We say that it is no worse to swear by the realities of nature as exemplified in the human body than to swear by a holy ghost. One is obscenity; the other profanity."

"Profanity is something that has become so widespread in its acceptance that it doesn't carry the weight that it did 20 or 30 years ago," Patrick, the prosecutor and professor, said.

Wolpe likewise asserts the widespread use of so-called swear words have lessened their impact: "Its purpose is to be shocking and powerful in speech at exceptional times," Wolpe explained. "Now that we've made it normal, even our profanity doesn't have the force that it should have."

The conservative Jewish cleric noted the overuse of God's name in casual ways signals "a loss to our society" of reverence and awe. (As an example, consider the now-conversational use of the texting abbreviation "OMG," for "Oh, My God," and how the full phrase often shows up in settings as benign as home-design shows without any recognition of its meaning by the speakers.)

"If nothing is considered sacred, then I guess the leveling reality of that is that everything is the same," Wolpe said. "There's nothing that people can treasure beyond the normal. You can't distinguish something as exceptional when everything is on the same level."

"People have been swearing for hundreds of years before there was television, radio," declared Tim Jay, a psychology professor at the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts and the author of "Why We Curse" and "Cursing in America."

"I don't think people learn how to swear from watching movies," Jay said. "In the surveys we've done, especially with people looking back at how they learned cursing, show that they learn from family, siblings and friends."

That said, Jay is willing to lay some blame at the feet of the media and technology: "We have a deeper cultural awareness of it because we are inundated with media. Television is on, news is on 24 hours a day; there was nothing like this in the 1930s. Everybody's got a phone or the Internet, so we reflect on these things."

An evolution

One area where Jay actively tracks the use of cursing is among the very young infants, toddlers and children. There, he says, the amount of cursing has remained constant over the past 30 years, which he and his wife Kristen, an assistant professor at Marist College in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., have confirmed in parallel studies.

"Between ages one and 12, we found progressive growth towards an adult vocabulary," Jay said. "Young kids, preschoolers, are focused on bodies, use 'poop,' and 'poophead,' which disappear as they get more adult-like language. We compared this with data in the 1980s, and overall, what we recorded 30 years ago is not a lot different than what we recorded a couple of years ago."

Does Jay believe cursing is a good thing for society? "I think, on an individual level, when you think of coping and venting, this is good for stress it's better than shooting or hitting each other," he said. "But, certainly, when you're looking at prejudice and bullying those aren't good."

Jay acknowledged some areas of society are clamping down: "Of course, we have laws that prohibit discrimination, harassment and threats," he said. "We have increased surveillance of workplace and school communications, (both) oral and written or electronic. Families who are religious uphold traditional standards; those less rigid probably have (more) relaxed standards."

The workplace is an area where experts are divided about the use of language. Jay said it's a way to let off steam and "build camaraderie."

But Diane Gottsman, an etiquette expert in San Antonio, in a blog about workers cleaning up their language, cited a 2012 Career Builder survey in which 57 percent of employers say they wouldn't hire a candidate who used profanity. And while some entrepreneurs lay down a strict no-cussing rule for their workplaces, CNBC reported earlier this year, a financial market insider affirmed to the network that cursing is quite prevalent in that environment.

"Wall Street is a hotbed of profanity," Dennis Gibb, a former trader at Morgan Stanley and junior partner at Bear Stearns, told CNBC. "You've got a lot of high-testosterone people with big egos making a lot of money."

Gottsman partly concurred: "I can definitely see that the times have changed. And we are exposed far more than in the past, in the good old days. One of the reasons it hurts us in business is that we come across as not having command of our language. That's why it's very important to use our words for power, and we lose our power when we start substituting strong words with profanity."

She added, "It all comes down to respect: if you wouldn't say it to your grandmother, you shouldn't say it to your client, your boss, your girlfriend or your wife."

Is Hollywood to blame?

And what about Hollywood, which is often blamed for coarsening the language?

According to Barbara Nicolosi, a Hollywood script consultant and film professor at Azusa Pacific University, an evangelical Christian school, lazy script writing is part of the explanation for the blue tide on television and in the movies.

"There's never one reason for things," Nicolosi said. "The dramatist's job is to create emotion in the audience. The artful way, the skilled way, of creating emotion is by successfully making audiences connect with the emotions at play and escape through the characters."

By contrast, she said, "Bad writers go for the emotional punch of crass language," hence the fire-hose spray of obscenities some modern films, almost regardless of whether or not the subject demands it. Martin Scorsese's "The Wolf of Wall Street," about a fraudulent broker, is littered with obscenities and might well reflect the industry upon which it is based; others saw a brief, profanity-laden segment of "The King's Speech" as unnecessary.

Nicolosi, who noted that "nobody misses the bad language" when it's omitted from a script, said any change in the industry has to come from among its ranks: "Writers need to have a conversation among themselves and in the industry where we popularize much more responsible methods in storytelling," she said. "It has to be organic, and a creative movement from within."

That change can't come quickly enough for Melissa Henson, director of grass-roots education and advocacy for the Parents Television Council, a pro-decency group. While conceding there is a market for "adult-themed" films and language, Henson said it may be smaller than some in the industry want to admit.

"The volume of R-rated stuff that we're seeing probably far outpaces what the market would support," she said. By contrast, she added, "the rate of G-rated stuff is hardly sufficient to meet market demands."

To support her claim, Henson noted the research of groups such as Movieguide, a Christian organization that rates films' family friendliness, and which consistently finds that "a PG-13 movie outperforms an R-rated one, PG-rated movies outperform PG-13, and G-rated films outperform PG (ones)." One reason is simple, she said: a studio can "make more money selling tickets to a family than just two tickets to a couple going out for date night."

Henson believes arguments about an "artistic need" for profanity are disingenuous.

"You often hear people try to make the argument that art reflects life," Henson said. "I don't hold to that. More often than not, 'art' shapes the way we live our lives, and it skews our perceptions of the kind of life we're supposed live."